Control your costs. Manage your expenses. Reduce spending. Lower overhead

These are phrases, or variations of it, that everyone has heard before at one point in their corporate career.

However, if there’s one thing about expenses that people often don’t realize is that you can’t control or manage them. You can only cut them.

That might appear to be just a play on words, but the difference is huge.

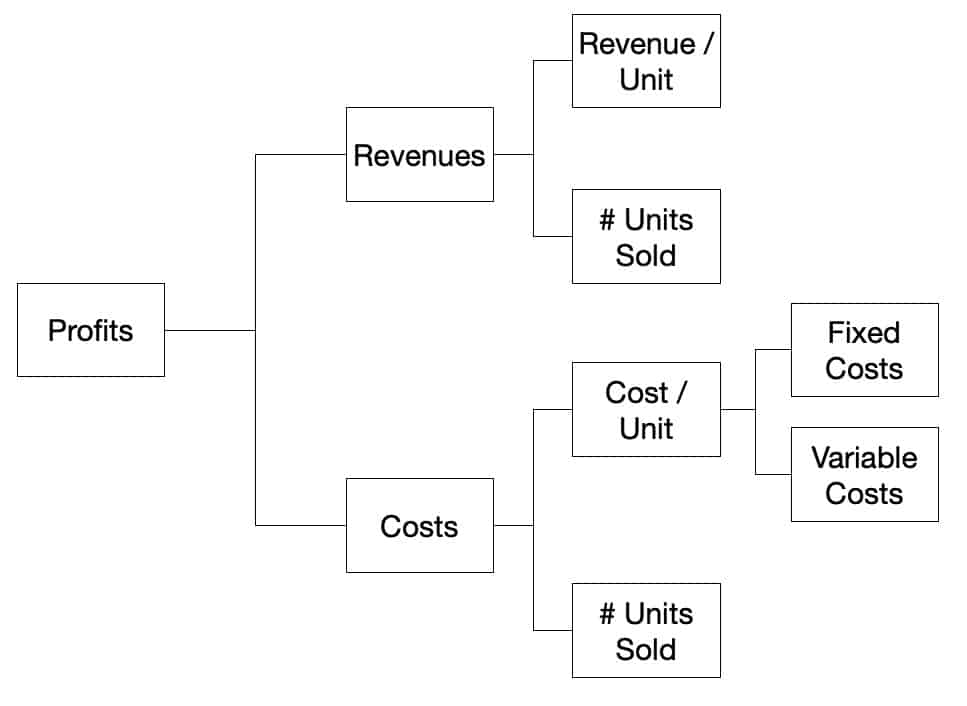

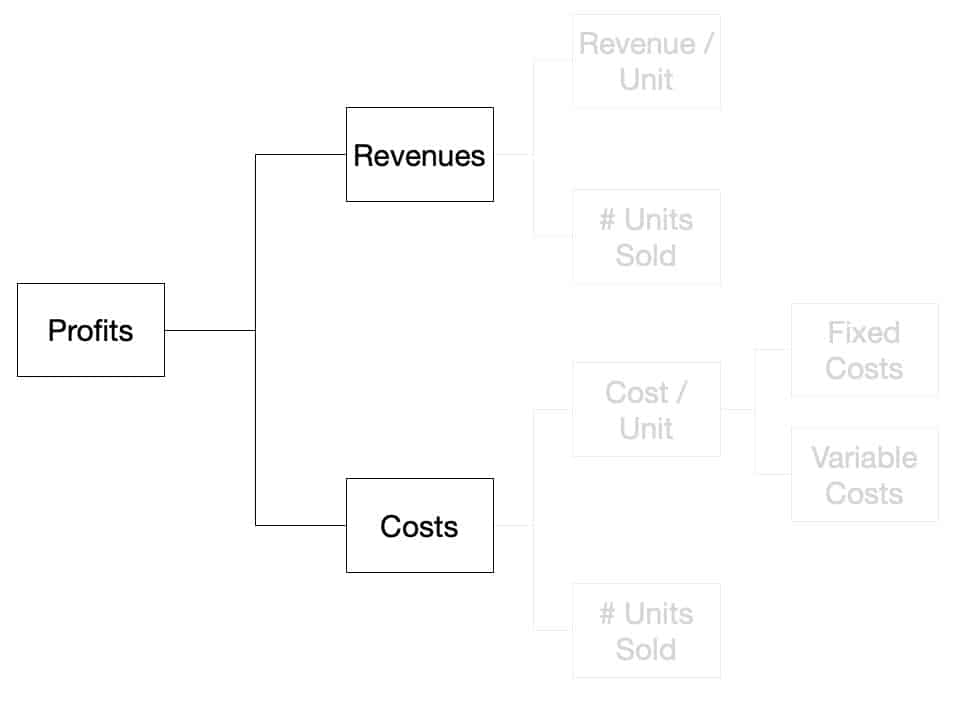

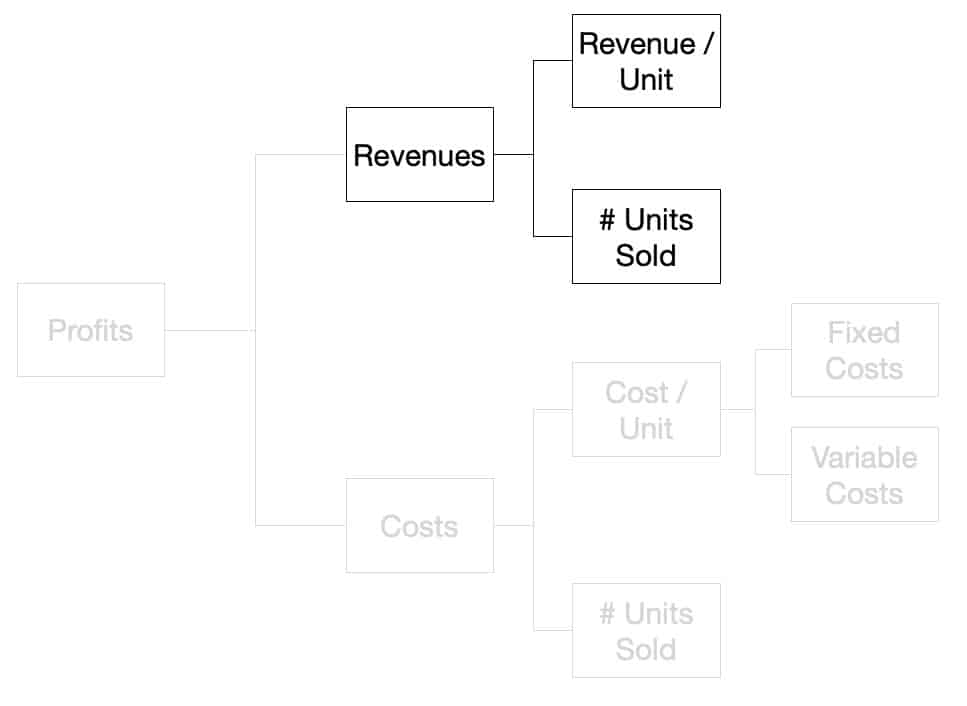

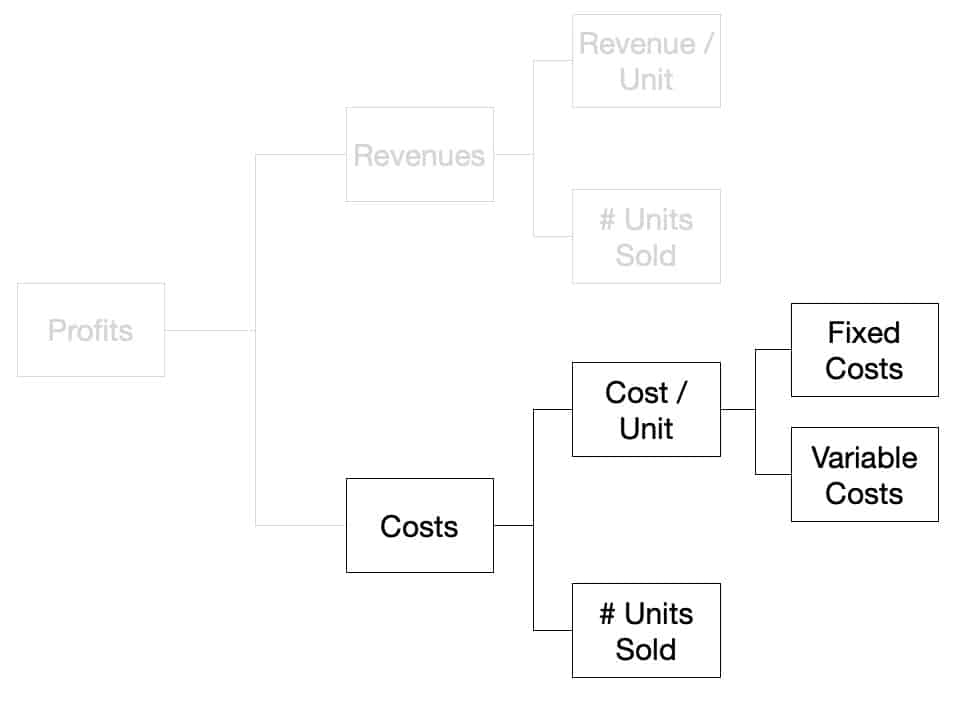

Costs (or expenses) are the second half of the profitability framework.

“The question should be: ‘Would the roof cave in if we stopped doing this work altogether?'” Drucker explained. “And if the answer is ‘probably not,’ one eliminates the operation. It is always amazing how many of the things we do will never be missed.”

The Danger of Managing Costs Instead of Cutting Costs

You might have probably guessed by now that I love Peter Drucker. He is arguably the most brilliant management consultant of our time. That’s also why he is revered as the father of modern management.

That aside, the approach to managing costs is finding ways to make things more efficient; while the approach to cutting costs is completely different.

Allow me to explain further.

Managing or controlling costs—becoming more efficient— doesn’t change the way you look at things. You accept the status quo and just improve on it, or at least find a way to improve the situation. This is why every time you do this exercise, it is very difficult to reduce the expenses.

On the other hand, to cut costs means you have to first “identify the activities that are productive, that should be strengthened, promoted and expanded,” said Drucker.

So, after identifying these value-adding activities, those that don’t add value, you cut them altogether. I included some guidelines on how to do that below.

This way of looking at cost is radically different than traditional methods of efficiency. Instead of simply looking for cheaper alternatives or putting pressure on suppliers to lower their prices, you re-evaluate everything.

Two Simple Examples in Businesses

Before that, here are two examples where the two perspectives differ:

Example 1: Monthly Events

Your organization conducts monthly recurring events. This can be anything from sales rallies to parties to general assemblies. If you wanted to only reduce your costs, most of the time, you look at alternative venues, cheaper food, or negotiate with the speaker, etc.

But if you are looking at cutting costs, you’d start looking at the results that these events bring in (if any). Or, if it’s even worth doing these events.

Example 2: Annual Conferences or Leadership Training

You frequently go or send people to conferences or training. If you want to manage your costs, you look for cheaper alternatives like different speakers, or maybe invite them to your office instead.

But if you look at cutting costs, you question the value of these conferences. Or figure out if they provide value at all.

Change before you have to.

Jack Welch

This shift in perspective is vital if you want change to really happen.

What’s important, Drucker said, is to make this a routine exercise — not something that happens only during downturns: “Businesses that actually succeed in cutting costs don’t wait until they have to cut costs.”

4 Key Questions to Ask and Answer

- Ask “what is our mission?”

- Ask “Is it still the right mission?”

- Ask “Is it still worth doing?”

- Ask “If we were not already doing this, would we now go into it?

1. What is Our Mission

Asking what your mission brings me back to my other article—what’s the purpose of your business?

How do you fit in the bigger picture? How is your business creating value in society?

The reason why this is so important is that without customers, your organization will cease to exist. If you are not able to create customers and keep them, you are not creating value.

One word of caution especially for tech-related businesses—don’t be blinded by the technology by itself. Technological innovation is not the same thing as value innovation.

2. Is It Still the Right Mission

The second question forces you to rethink the value you are delivering.

Put this in another way, are you delivering any value at all? Remember, the more technology is involved in your organization, the higher the tendency to believe that you are creating real value to your customers.

It might also be that you have delivered value before have become complacent to the ever-changing needs of the market. These are the Blockbusters, Kodaks, and Polaroids.

They have become leaders in their own markets and provided a lot of value. But over time, they think that their market leader status was unmovable.

3. Is It Still Worth Doing

This next question can mean two things: (1) it can refer to the mission, or (2) it can mean about this activity that you want to look at. Basically, you ask if this “thing” that you are doing worth it?

Going back to my example above, if the events were being conducted but aren’t really adding value, then why do it?

- Because it’s tradition

- We’ve always done it this way.

I can tell you now that these are terrible answers.

One specific example comes to mind every time I ask this question to myself. Back when I was working in one of the subsidiaries of a company with over 700+ employees, I noticed some reports that took a few hours a month to make weren’t being used. No one was actually reading them. They were redundant reports that were a small subset of a bigger report which was the one being used.

Obviously, this was a big waste of time for the people doing it. But, until I have pointed it out, they were doing it just because that’s the way it has always been.

4. If We Weren’t Already Doing This, Would We Now Go Into It

Finally, this question makes you rethink about things you want to do or change. Most of the time, we feel that what we are doing isn’t enough. By asking this question, you’d know if introducing this activity (usually accompanied by costs) is worth even trying.

“The overall answer” Drucker added, “…is almost never ‘This is fine as it stands; let’s keep on.’ But in some – indeed a good many – areas the answer is, ‘Yes, we would go into it again, but with some changes. We have learned a few things.’”

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.

Albert Einstein

Bonus Example

Earlier I shared two examples without going into the details of cutting costs. Now that you’ve understood the 4 questions you can ask, here’s another example where you can apply those questions: perks.

Perks can range from free meals to higher benefits, to sports programs. Anything under the sun that the company provides for its employees.

Oftentimes, these are argued to increase productivity and foster camaraderie, and as part of employee engagement. That’s why businesses have budgets for them.

The key point here is determining what value are they adding? Are they really making your people more productive and motivated? Do the perks attract more potential hires and retain current employees? Does it really help collaboration across different teams? The list goes on.

Conclusion

Managing costs is different from cutting costs.

If you’ve followed the works of Drucker, and I suggest you do especially if you are in a leadership position in your organization, he always puts things into a bigger perspective. It’s not just about making money. It’s not just about your company. It’s always the customer and how you are creating value for them.

These four questions allow you to evaluate which activities are value-adding and which are not. You “double-down” on these value-adding activities and cut the ones that don’t.

Force yourself to ask these questions over and over to make sure you are still doing the right things. Or put it in another way, to make sure that you are still delivering value to your customers.